A pioneering painter who also taught at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Damascus between 1966 and 1987, Moustafa Fathi (1942-2009) was widely respected for his research of Levantine folk art in addition to his analysis of Syrian visual culture as a complete record of social advancement that stretched back to ancient times. One of the central ideas that Fathi identified in his reading of history was a profound connection to nature, particularly the diverse landscapes that shaped Syrian society as communities adapted to surrounding environments amidst political shifts—a relationship to the land that was articulated in various art forms. Although modern painters detailed the historical, cultural, and environmental factors that continued to shape the Syrian experience, Fathi was the first artist to reconfigure the aesthetic motifs that emerged over centuries of social development by returning to a basic structure from which new forms could be derived.

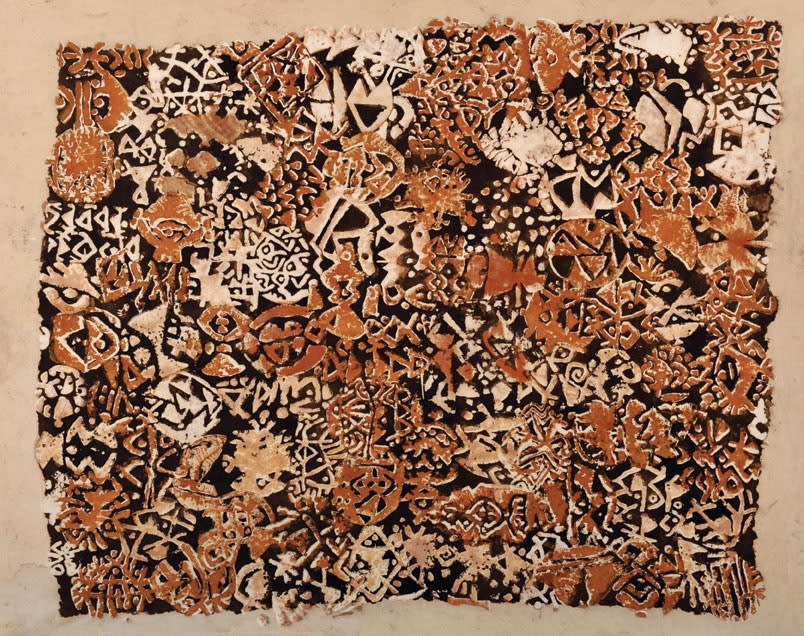

Recognizing that human thought stems from abstract concepts, Fathi likened the process of invention in language, art, philosophy, and so forth to the growth processes or “mechanics” of nature. Fathi demonstrated this theory by treating each painting as a site where regenerated forms organically emerge. Using a printing method that registered intricate cells of lines and shapes, Fathi allowed the different characteristics of his self-contained patterns to interact, eventually creating a dense grid of colliding or overlapping units as he intuitively positioned them within rectangular compositions. Vertical paintings reminded the artist of a written page while horizontal works resemble the arrangements of objects such as artefacts, rocks, and animal bones that were sprinkled across the floor of his studio as he mapped the layers of Syria’s terrain that accumulated over time.